Samuel Hubbard Scudder loves bugs. In fact, he loves them so much that he is prepared to make entomology (that’s the study of insects) his life’s work. That’s why he’s about to embark on a degree program at Harvard’s highly respected school of science. It’s the late 1850s. By the time of his death in 1911, Scudder will become widely known and respected for his work, especially his study of grasshoppers.

But for now, in his early twenties, Scudder is an earnest young scientist, eager to learn all he can. And Scudder has the opportunity to learn from the very best—Professor Louis Agassiz. But the first interaction between student and professor will go a bit differently from what Scudder may have imagined.

Professor Agassiz is enthusiastic, eccentric, and prolific. Born in Switzerland, he has traveled the world and now finds himself at the head of the science school at Harvard. Agassiz has revolutionized the study of fish fossils; he has published a substantial stack of volumes; he has lectured and written about his controversial ice age theories; and he has received multiple honors for his scientific work. And he’s just getting started. His ideas will make him famous (and in some cases infamous) and scientists and historians alike are still talking about him today.

When Agassiz’s brand new student, Samuel Scudder, steps into the professor’s laboratory for the first time, he sees glass jars filled with all sorts of biological samples. He notices the unpleasant stinging odor of preserving alcohol that hangs in the air. But mostly, Scudder notices the professor. Agassiz’s face is open, almost childlike. He’s balding, but there is an intensity and playfulness in his eyes that shows that age is doing little to slow him down.

Scudder introduces himself respectfully and expresses his intentions of studying with Agassiz at the school. After grilling Scudder about his education, asking him why he has come, and asking what he will do with what he learns, Agassiz shows his satisfaction with Scudder’s answers by asking, “When do you wish to begin?”

“Now.”

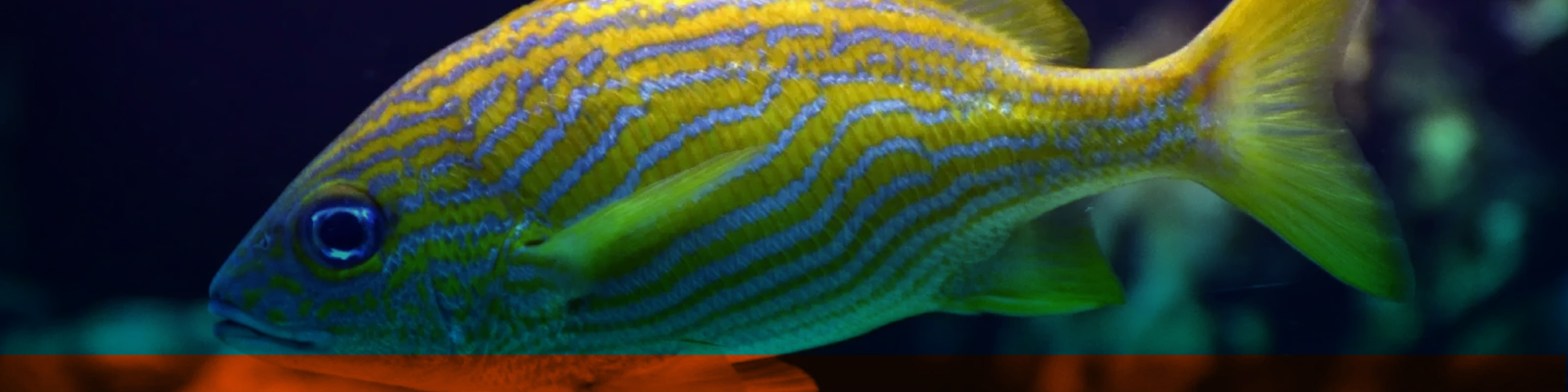

“Very well! Take this fish, and look at it; we call it a haemulon; by and by I will ask what you have seen.”

Agassiz explains to Scudder how to properly care for his specimen. For the sake of examination, the dead fish has been removed from its jar and placed on a tin tray. Whenever it starts to dry out, Scudder will need to splash some of the alcohol from the jar on the fish to moisten and preserve it.

After dispensing these instructions, Agassiz strides out of the room leaving Scudder alone with his fish. Agassiz makes it clear that Scudder is not to use a magnifying glass or other instrument, nor is he to consult any textbook or scientific guide. It must simply be Scudder and the fish.

Obediently, Scudder examines the fish, carefully noting its features, eager to make discerning observations he can pass along to the professor.

A full examination of the specimen takes Scudder about ten minutes so he goes in search of Agassiz… only to find out that he has left the building.

Scudder returns to the laboratory, where he looks around, examining some of Agassiz’s other specimens. But he realizes that, with no further direction from the professor, he can only ultimately do one thing—return to his examination of the fish.

The more Scudder looks at it, the uglier the fish seems to become. He looks at it from every angle, but it’s still just a fish—a fish that Scudder is growing to hate. After two hours of tedious examination, Scudder lets himself take a break for lunch, happy to be free for an hour. When he gets back, he learns to his dismay that Agassiz has come and gone and won’t be back for a while.

Out comes the fish.

In desperation, Scudder starts to get creative. He feels inside the fish’s throat. He even tries counting its scales. Then a thought strikes him. Why not draw the fish?

The professor did not forbid the use of paper and pencil, so Scudder fetches them and starts to sketch. That’s when Agassiz returns.

“That is right, a pencil is one of the best of eyes. I am glad to notice, too, that you keep your specimen wet, and your bottle corked. Well, what is it like?”

Scudder does his best to name off the fish’s features. He describes the shape of its head, the nature of its gills, its mouth, its eyes, its fins, its tail.

Agassiz listens closely, but when Scudder is done, he looks disappointed.

“You have not looked very carefully; why, you haven’t even seen one of the most conspicuous features of the animal, which is as plainly before your eyes as the fish itself; look again, look again!”

It’s the last thing Scudder expected. Just when he thought he would be rid of the vile fish, Agassiz is telling him to examine it even more closely.

But Scudder sets aside his disgust and returns to his observation. The professor’s rebuke has motivated him. He quickly finds that he has, indeed, failed to observe many of the fish’s features.

And so the afternoon passes. As evening approaches, Professor Agassiz asks hopefully, “Do you see it yet?”

“No, I am certain I do not, but I see how little I saw before.”

“That is next best, but I won’t hear you now; put away your fish and go home; perhaps you will be ready with a better answer in the morning. I will examine you before you look at the fish.”

Scudder spends a fitful night. All he can think of is the fish.

In the morning, Agassiz greets him warmly, eager to see if his new student has discovered what it is he missed the day before.

Timidly Scudder offers, “Do you perhaps mean, that the fish has symmetrical sides with paired organs?”

“Of course! Of course!” Agassiz launches into an enthusiastic lecture about the importance of this specific biological trait. Scudder listens patiently, then asks the professor what he should do next.

“Oh, look at your fish!”

And so he does. For three days, Scudder does little but examine that fish. Again and again, Agassiz exhorts him to “Look, look, look!”

On the fourth day, Agassiz brings out another fish and tells Scudder to compare the two. Another fish follows, and then another, and then another. Scudder compares and contrasts them all. At Agassiz’s direction, he begins to dissect them and examine their organs and skeletal structures.

Finally, months later, Agassiz finally declares the study of the fish to be complete. He allows Scudder to turn his attention to his beloved insects.

But Scudder comes to appreciate Agassiz’s unusual teaching method. Years later, Scudder recalls Agassiz’s repeated injunction to “Look, look, look!”, and Scudder says fondly, “This was the best entomological lesson I ever had—a lesson whose influence has extended to the details of every subsequent study; a legacy the Professor had left to me, as he has left it to many others, of inestimable value, which we could not buy, with which we cannot part.”

“What must I do next, Professor?”

“Oh, look at your fish!”

Just look at your fish.

My family recently visited Charleston, South Carolina. While we were there, we went to Fort Sumter, the site of the first shots of the American Civil War. While at Fort Sumter, we saw a lot of cannons. But as we walked by one of those cannons, a park ranger stopped my sons and asked them some questions. First, he asked them to look for a tiny hole on top of the cannon near the back. With a little time and a little help, they found it. He explained to them how this small hole was an important part of firing the cannon. He then went on to have them come around to the front of the cannon and feel the inside of the barrel. He explained that the grooves they could feel were designed to spin the shell as it moved down the barrel of the cannon, allowing it to fly farther.

I’m pretty sure most of what he said went right over their heads, but after that, they noticed some of those same features on other cannons. His encouragement to look closely at the cannon opened their eyes to what was already there. We saw a lot that day. We gave most of what we saw little more than a passing glance. But when that park ranger encouraged us to stop and look—that’s when we started to learn something.

From time to time, I’ll have people ask me what resources I find most helpful in my study of God’s Word.

It’s almost embarrassing how many resources I have at my fingertips: Bible dictionaries, concordances, commentaries, word studies, books on the geography and culture of Bible times… the list could go on and on and on.

I have shelves full of Bible study aids. People who are much more smart and capable than I am have created some really helpful resources. And sometimes, I recommend one or two of those resources to others. But when someone asks me what they can do to improve their Bible study, my primary goal is to encourage them not to be too quick to look away from the Bible in search of some other resource. I want them to read their Bible and study it and examine it.

When someone is studying their Bible and they ask me, “What should I do now?”

I want to tell them, “Look at your Bible.” Read it again and again. Study it until you begin to discover the truths you missed the first, and second, and third time you examined it. And when you’ve found everything there is to find, look again! Because there’s more.

In James chapter 1, we get a simple word picture that describes our relationship with God’s Word.

“If any be a hearer of the word, and not a doer, he is like unto a man beholding his natural face in a glass: For he beholdeth himself, and goeth his way, and straightway forgetteth what manner of man he was.” (James 1:23-24)

A mirror does you no good if you don’t act on what you see!

But we don’t have to be those who read the Word and ignore what it says. James goes on, “But whoso looketh into the perfect law of liberty, and continueth therein, he being not a forgetful hearer, but a doer of the work, this man shall be blessed in his deed.” (James 1:25)

What is it that sets apart the one who is obedient to God’s Word from the one who forgets and ignores what it says? James says that the one who obeys is the one who continues. God’s intent is that, when it comes to His Word, we will look, and look, and keep on looking.

It can be tempting to read books about the Bible instead of reading the Bible—to depend on Bible study writers to do the studying for us. But is it healthy for us to settle for reading devotionals instead of reading the Bible?

It can be easy, when we come across a difficult passage or a verse that doesn’t immediately make sense to us to quickly pull up a Bible website or open our favorite commentary looking for answers instead of taking the time to examine it carefully for ourselves.

All those resources have their place, but we would all do well to spend more time—just us and our Bibles.

Louis Agassiz was quick to encourage Samuel Scudder, not to read books about fish, but to look at the fish itself.

We must be quick, not just to read books about the Bible, but to study the Bible itself.

Do you want to know what to do next?

Look at your Bible.

Look, look, look.

Learn More

Read Scudder’s account of his study of Agassiz’s fish.

Learn about Louis Agassiz.

Learn about Samuel Scudder.