Horatio Spafford’s blood runs cold. His ears must be deceiving him. He looks at his wife and sees a look of hurt bewilderment on her face that exactly mirrors the emotions swirling in his own heart.

“I’m sorry. What did you say?”

His visitor shifts in his chair, then says, earnestly, “Yes. I… I’ve come to offer to… adopt your daughter… as my own.”

Has it really come to this? Horatio wonders. Has my life really sunk so low?

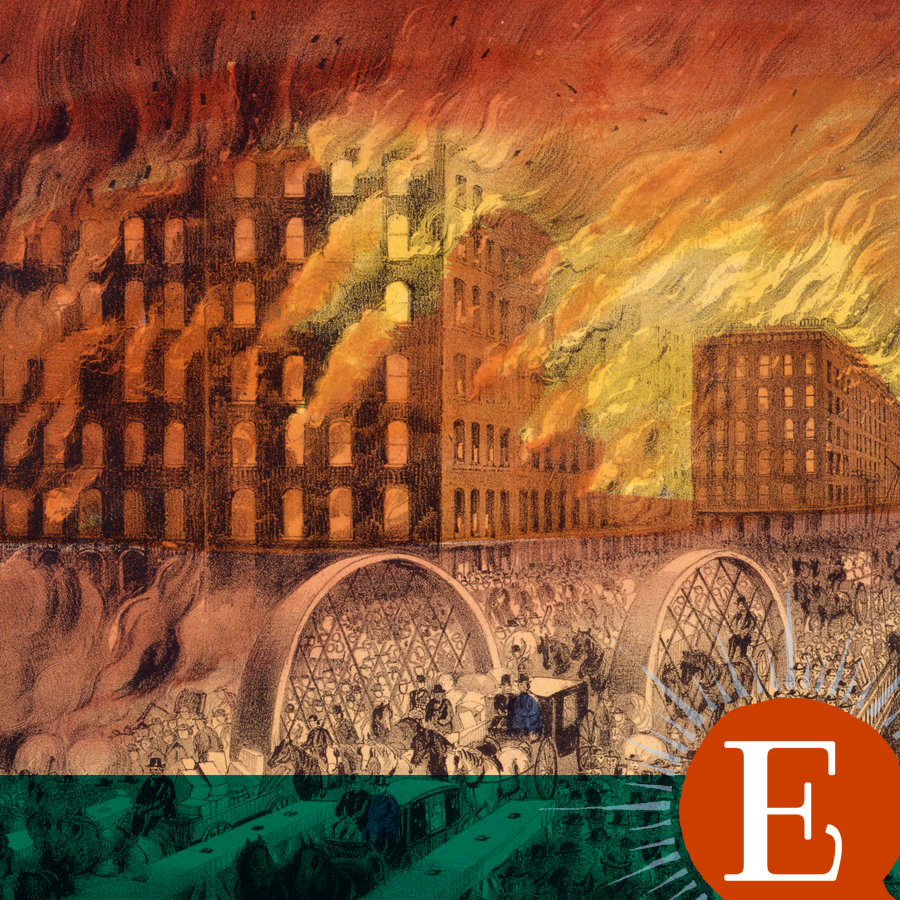

It was a dark night and we were all in bed. Ms. O’Leary’s cow kicked over a lantern… and the rest is history. The truth is, it probably wasn’t the cow’s fault, but in October of 1871, the city of Chicago was devastated by a mammoth fire that started in a barn belonging to Patrick and Catherine O’Leary.

The damage caused by the blaze was catastrophic. Flames continued to burn for more than 24 hours, leaving four square miles of the city destroyed. Hundreds lost their lives and tens of thousands more lost their homes or businesses. Among those whose lives were profoundly affected by the fire was a Christian businessman named Horatio Spafford.

Though the Spafford home was spared, nearly everything about life seemed to have changed in a matter of hours and Spafford decided to send his wife Anna and their four daughters to Europe to get away from it all. He stayed behind, promising to join them soon, looking forward to sharing a joyful Christmas in France.

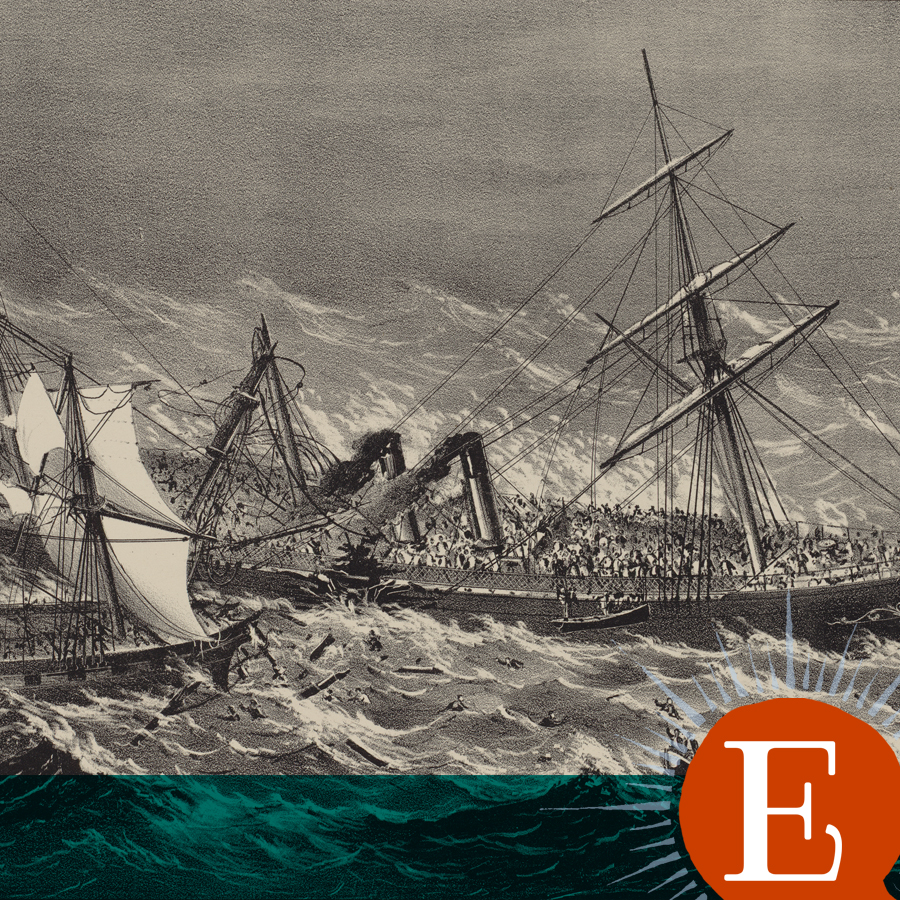

But Spafford would never see his daughters again. They died at sea when their ship collided with another during the crossing. When he received the shocking news, Spafford was nearly paralyzed with grief. But despite sorrow being piled on loss, Spafford maintained his faith in God. As he crossed the Atlantic to join his wife, he penned the words to one of our most beloved hymns after crossing the spot where his daughters’ lives had been lost to the waves.

“It is well, it is well with my soul.”

Horatio and Anna are reunited. Numbed by the pain of their bereavement, they feel at a loss about what’s next. But time, as it will, continues to flow on.

The return home is almost more than the Spaffords can bear. To walk into the home with all its monuments to their little girls’ lives, so unexpectedly snuffed out, is like a thousand daggers to the heart. Horatio and Anna find some solace in serving others. Anna gets involved with ministry to women. Horatio helps financially and uses his gifts as a poet to serve the hearts of others.

Joy follows grief when in 1876 and 1878 Horatio and Anna welcome a son, Horatio, and then a daughter, Bertha, to their family. It must seem that their sorrows are finally behind them. The future, surely, must be brighter.

But the shadow of tragedy continues to follow the Spaffords. In February of 1880 little Horatio and Bertha suddenly sicken with scarlet fever. Their father rushes home from a business trip, arriving only just in time to watch his little son, and namesake, die.

The crowd at the graveside is small. Horatio presides over his own son’s funeral while his wife stays home with little Bertha who is still battling the fever. After the funeral, Anna cannot bring herself to visit her young son’s grave. Horatio and Anna do little to show outward grief, but this latest bereavement leaves them reeling, struggling not to doubt God’s grace, determined not to lose faith.

As Anna puts it, “I will say God is love until I believe it.”

To augment their sorrow, gossip begins to spread. Some fellow believers interpret the Spaffords’ sober, stoic manner as hardness of heart toward their own son. Questions arise about whether it is some sin in Horatio and Anna’s lives that has led to wave after wave of sorrow. Is all this trouble and loss a punishment from God? Some wonder if the couple are fit to be parents at all.

One day, a friend from the church stops by the Spafford home. It is not his first visit to the house. He is one of the leaders of a group that had met in their home many times before. He comes with a proposition.

Would the Spaffords like him to adopt Bertha?

The offer comes as a complete shock. Little two-year-old Bertha is the only child left to Horatio and Anna of their six. Now someone is trying to take her away? The request comes like a slap to the face and it helps Horatio and Anna reach the conclusion that nothing remains for them in Chicago.

They will go to Jerusalem.

The couple has long dreamed of making the trip. Horatio is deeply interested in prophecy. He has poured over the prophetic books of the Bible, looking for hidden insights and growing in his confidence that Christ’s return is very soon. Perhaps, they will even be present in Jerusalem to watch prophetic events unfold.

Spafford has also reached the false conclusion that there can be no such thing as eternal punishment in hell, a position that puts him at odds with the church he and his family have long called their own. A controversy follows which leads to a formal request that the Spaffords remove their membership from Fullerton Avenue Presbyterian Church. Several other families, loyal to their long-time friends, leave the church as well.

Some of these families accompany the Spaffords to Jerusalem and together, they form what will come to be known as the American Colony. Some call them a cult, others laugh it off as an attempt at utopia. It is even rumored that Horatio Spafford thinks himself the Messiah. In truth, the majority of the rumors are totally false. The group is mostly engaged in humane work among the diverse ethnic and religious groups that inhabit Jerusalem.

Jerusalem will become home for the Spaffords. There they will raise their daughter Bertha and another daughter, born just months before their departure.

After the baby’s birth back in Chicago, as Anna lies recovering, she wonders what they ought to name their new daughter. Her eyes fall on an illuminated text that hangs on the wall. It is quotation from 2 Corinthians 12.

“…My grace is sufficient for thee…” (1 Corinthians 12:9)

The baby’s name will be Grace.

In Job 16, after fourteen chapters of wearisome arguments, Job finally comes out and says it.

“…miserable comforters are ye all.” (Job 16:2)

His friends have tried to discern his motives, they have tried to critique how he is grieving, they have asked him to admit the sin he has committed to deserve such judgment from God. These responses may be natural, but they are all profoundly unhelpful. When we consider someone who is grieving, we can be tempted to think more about ourselves than about our grieving friend. This leads us to think and say foolish things. What those grieving need more than anything else is not a critique, not a solution, not an explanation, or a little sermon about how it’s all for the best. They need grace.

We can wag our fingers at the members of the Spaffords’ church for how poorly they responded to Horatio and Anna’s grief. But it can be easy to become the same sort of miserable comforters. Grief is a complex and difficult thing. The best comforters are generous, they are patient, and they model Christ’s love.

Horatio Spafford’s story is complicated. Understanding more leaves me with a question. What do we do with “It is Well With My Soul”? After all, Spafford took a bit of a left turn with his theology. What do we do with a hymn written by a man who denied the doctrine of eternal punishment, who had some unorthodox views of prophecy, and whose theology is, at best, a bit hard to pin down in his later life?

To give a simple answer to a sticky question, I ask you to consider with me a king named Solomon. Solomon was by no means a shining example either of morality or theological purity. He literally oversaw the building of temples to false gods and potentially personally engaged in pagan worship to these deities.

But God put Solomon’s writings in the Bible.

That is not to say that the source of something doesn’t matter, but we do not benefit from the poetry, musicianship, or oratory of believers from the past because they were perfect. A close inspection would likely reveal that all of our “heroes” of the faith are much less heroic than we might think. But as long as they hold forth the truth and point our eyes to Jesus Christ, they can be a help to us.

So I say, thank God for Horatio Spafford. Thank God for It Is Well With My Soul. Because as we sing the sweet, rich words of this hymn, we find our eyes turned, not to a man, but to His God.

“For me, be it Christ, be it Christ hence to live

If Jordan above me shall roll,

No pang shall be mine, for in death as in life

Thou wilt whisper Thy peace to my soul.”

Learn about the Great Chicago Fire (National Geographic)

Read about the Spaffords and the American Colony:

Our Jerusalem: an American Family in the Holy City, 1881-1949 by Bertha Spafford Vester

Well with My Soul: Four Dramatic Stories of Great Hymn Writers by Rachael Phillips